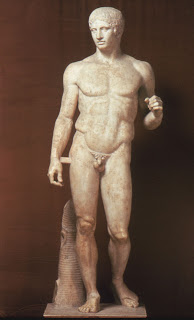

The Spear Carrier shows the relation to man to the world as one of self-confidence. It represents a frank extension into art of man's own ego, and signifies its creator's concern with the here and now, not his speculation on vague, mystical subjects or death. What in Homeric times had been remote, distant, and feared was brought within man's ken and perception. The Classical nude thus reflects a man-centered world, one where man is the focus and measure of all things.

The Classical Greek figure without clothing must be termed "nude" rather than "naked." The latter term suggests shame, self-consciousness, an unaccustomed state. The nude figure instead is one perfectly at ease without garments. For the Greeks, the ideal of nudity separated them from the barbarians. They had no sense of sin or shame in respect to the unclothed body.

The balance and rhythm of the Spear Carrier signifies not only control of the body but the training of the mind and the Apolline values of moderation. The Classical view of beauty depended upon a subtle manipulation of opposites. The fifth-century "beauty pose" showed a condition of rest tempered by movement, a balance between perfect energy and perfect repose. The artistic device that permits the capturing of this dualism was counterpoise; that is, for every movement in one direction, there is a countering tendency in another.

In form and meaning, the figure of Isaiah is the antithesis of the Spear Carrier; in purpose, however, the two are similar. Both are concrete realizations of human beliefs, which presented the viewer with ideal modes of being in the guise of heroes greater than himself. The Christian figure testifies to the existence and superiority of a spiritual world transcending the mundane sphere of the viewer.

The spear carrier is an athlete in the usual physical sense; Isaiah, an athlete of the spirit. The movement and proportion of Isaiah was directed in its appeal less to the eye than to the mind. There is an excitement in the prophet's pose, a sort of spastic and unself-conscious total gesture that mirrors his spiritual intensity.

The rational attitude and sensory experience of the Greek artist, which he animated his optimistic figures, was alien or untenable for his Gothic counterparts. The bodies of the Gothic saints comprise refuges from the uncertainties, tensions, and anxieties of the natural world. There is no hint of the repose and relaxation emblematic of man's concord with himself, with his society, or the world. The Gothic world could not accept the outlook of the Greeks.

Similarly, Donatello's Mary Magdalen sculpture is a merciless study of the body made less than human, first through self-indulgence and then through a self-denying asceticism. He renewed the late medieval dichotomy between inner truth and surface beauty (status change). The Magdalen has become a living corpse, like a medieval reminder of death and the wages of sin. Only the zeal of the convert animates the leathery flesh of this skeletal figure, holding out the same hope as baptism. The spiritual intensity imparted to the sculpture by Donatello transcends its physical repellence and makes the work esthetically compelling. The slight gap between the hands creates a life-giving tension that complements the psychological force emanating from the head.

No comments:

Post a Comment