Saturday, July 31, 2010

abstraction is "the essence, or real sense of things"

After the torso' rediscovered in the Renaissance, it gained partial-figure concept developed by Rodin, who in turn had derived his inspiration from such ancient fragments as the Belvedere Torso. Constantin Brancusi stripped his body to a point where its shapes have been generalized into a few cylindrical volumes. (Despite its title, the ambiguity of its gender creates of this sculpture a kind of "impartial" figure.) Simplification to the point of absolute reductiveness was the means by which he thought his art could approach the essence, or "real sense," of things (and naturalistic sculpture isnt real?). At a certain point in the process of reductiveness, as Brancusi found, the body can become associated with other, nonhuman shapes of a botanical or technological character, depending in part upon whether the material was wood or bronze. (This piece can be exhibited successfully even if inverted, something wholly impossible in naturalistic art.) Thus a plurality of associations, which broaden the frame of sculptural reference, are possible. Brancusi had no desire to emulate what he called the "beefsteak" of the Belvedere Torso or the sculptures of Rodin. His final surfaces are the outcome not of modeling but of rubbing and polishing. By reducing the torso to elementary but kindred and still sensual shapes, he was able to achieve sculpture that was for him perfect in its proportions and over-all concordance.

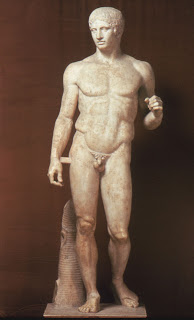

Hans Arp's Human Lunar Spectral has certain affinities with the Belvedere Torso and yet remains suggestively ambiguous. The torsion of the former recalls the flexibility of the Greek work but lacks any definite evidence of spine, pelvis, or muscle. There are also affinities in the lower portions of both; but Arp's form gives no hint of a skeletal or muscular substructure. Both Arp and Brancusi helped introduce into modern art a "sculpture without parts." Unlike Brancusi's torso, that of Arp seems capable of growth or swelling and contraction, thereby having greater reference to organic life. Rodin had defined sculpture as the art of the hole and the lump, yet as something always tied to the body's configuration.

Arp gave a purer and more obvious demonstration of sculpture as a logical succession of pliant concave and convex surfaces enclosing a volume. The rightness of this sequence is measurable not against the standard of the human body but only in terms of the sculpture itself.

Sculptors since the Egyptians and Greeks had frequently used the human body to personify some aspect of nature. (The Greeks used reclining male figures as river gods.) Modern sculptors such as Arp and Henry Moore have tended to see the body in terms of nature and to fuse qualities of both into a single work, thereby suggesting the unity of all life.

.jpg)

Woman receives a new life and serenity in the work of Henry Moore. In terms of the problem of disparate and unevenly distributed shapes referred to previously, Moore transformed the body to effect a more satisfactory sculptural balance, consistency, and continuity. When Moore reduced the size and definition of the head, eliminated the feet and hands, fused normally distinct or unconnected body parts, and introduced a great hollow in the middle of the torso, he was not motivated by a superficial desire to shock. His rephrasing of the body and investing it with a tissuelike surface created strong and fluid rhythms that for him suggest linkages of man and nature. His reclining forms of wood and stone seem shaped—that is, smoothed down—by the corrosive and abrasive action of the elements. The reclining pose had been traditionally associated with tranquillity and dignity, and these connotations were still honored. The living body possesses many openings, and Moore's use of hollows derives from mixed associations, from esthetic and sexual reveries centering on the inner cavities of the body, the womb, as well as fantasies and inspiration from caves and holes in wood and rock. His personal image exalts qualities and processes sensed, if not seen, in the body and elsewhere in nature.

a big step toward abstraction

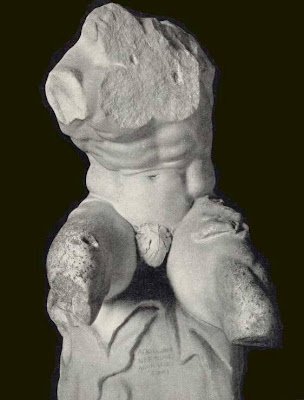

One of Rodin's most dramatic contributions historically was his demonstration that parts of the body were dispensable in a finished sculpture. In 1900 he exhibited publicly for the first time a small headless and armless study made for his John the Baptist. Some years later he enlarged this work and gave it the title Walking Man. Inspired by his study of the fragmented figures of antiquity in museums, Rodin became convinced that a complete work of art did not presuppose an entire figure. He cited the example of portrait busts and pointed out that in Greek fragments we can appreciate perfect beauty (a premise to which the Greeks themselves would have objected). When Rodin eliminated the head and arms from his sculpture, he also removed its identity and the traditional means for rhetorical expression. As pedestrian a subject as a man walking now took on the aspect of universal drama, and for the first time biological man became the central artistic concern. From certain angles the Walking Man, in full stride and with the upper part of his torso tilted forward and to the right, appears about to topple over. The powerful legs suggest a pushing off from the back foot and a receiving of weight and downward pressure on the front foot—a simultaneous condition that is impossible in life yet believable in Rodin's sculpture. Like Michelangelo, Rodin was willing to adjust anatomy in the interest of artistic plausibility. When asked why he had left off his figure's arms and head, Rodin replied, "A man walks on his feet."

greek vs gothic sculpture

The rational attitude and sensory experience of the Greek artist, which he animated his optimistic figures, was alien or untenable for his Gothic counterparts. The bodies of the Gothic saints comprise refuges from the uncertainties, tensions, and anxieties of the natural world. There is no hint of the repose and relaxation emblematic of man's concord with himself, with his society, or the world. The Gothic world could not accept the outlook of the Greeks.

The Age of the Infovore

Friday, July 30, 2010

myth is neither allegory nor philosophy but identification

Within myth, the faithful hardly believe in anything; they simply and unself-consciously respond to the world they perceive with the aid of the myth, a world, moreover, that they see as real. The beliefs we observe in others are, for the insiders, invisible and taken for granted. The fan does not believe the Red Sox are the best team; he knows it. The devout don't believe Jesus is the Christ; they encounter Jesus directly as the Christ. The myth implicitly presents the world as it is, not as it may possibly be.

When the believer says, “There is no God but Allah and Muhammad is His Prophet,” he is bearing witness, to the facts as he sees them, as realities in the universe not belief in his mind.

Myth can convey meaning and purpose, but it does so with a price and a danger. That’s what it looks like from the outside. But from the inside, it doesn’t look that way. From inside of myth, we become more authentic, and life gains greater significance and meaning, the more we identify with the mythic tale.

What constitutes a worthwhile life?—cannot be asked while we are living mythically. From inside myth, the question of meaning never arises. All myth can do is tell compelling stories. To ask critical or abstract questions of a myth—how the stories are related or what ideas they represent, for example—is already to violate the mythic mind. Myth is neither allegory nor philosophy but identification. The most important thing about myths is not the depth of ideas they contain— remember, I said they calm the mind precisely by staying on the surface of things—but whether they are compelling. To remind a companion who emerges in tears from a viewing of The Last Picture Show or some similarly sad movie that "It's only a story; it's not real" is both to miss the point and to misunderstand the compelling nature of, and total identification with, myth.

We begin to ask why and what for when faith and myth become self-conscious. Mythic thinking breaks down whenever we become reflective or self-conscious. Meaning is the price we pay for self-consciousness.

Faith over belief: "People say that what we are all seeking is a meaning for life. I don't think that's what we're really seeking. I think that what we are seeking is an experience of being alive, so that our life experiences on the purely physical plane will have resonance with our innermost being and reality, so that we actually feel the rapture of being alive. That's what it's finally all about."

- Joseph Campbell

belief vs faith

However important knowing the characteristics of myths may be, we miss something essential if we do not distinguish between knowing about myth and living mythically. The word about connotes a separation between the knower and the known that is alien to genuine myth. One can formulate propositions that are either true or false about an object. Persons outside a myth can characterize and describe myth, as I am doing here, but knowing about a myth is different from living from within it. I may know all the statistics of the Atlanta Braves baseball team—how many games they've won and lost, their team batting average and ERAs—but that is different from being a fan who identifies with the team and the mythology of baseball.

What separates a fan from someone who knows about—one who is inside a myth from one who is outside—is emotional identification, ritual, and imaginative reenactment. The fan identifies with the team and its heroes. The fan is happy when the team wins and is despondent when it loses. Similarly, the person living within a myth identifies wholly with the characters and events of the myth. Eric Havelock emphasizes that the ritual oral performance and retelling of Greek myth elicited an active, hypnotic identification of the audience with the myth. The audience was not merely watching a performance of a myth; it was ritually engaged in a reenactment and identification with it. In these circumstances, audience and performer become one. Within myth, I do not think about Achilles; rather, I wholly identify with Achilles; in a sense, I become him, as long as I submit myself to the incantation. This fanatical identification with the myth annihilates my autonomous, separate ego. I no longer live "as if" but in and within the myth.

The absolutely critical distinction between knowing about myth and living within myth is clarified by Wilfred Cantwell Smith's discussion of faith and belief. Belief is analogous to knowing about. It is both propositional and provisional. Belief is "the concept by which we convey the fact that a view is held, ideationally, without a final decision as to its validity. Thus, it is reductionistic. Belief rests between complete skepticism, on the one hand, and certain knowledge, on the other. From the outside, we say of someone that they believe in, rather than know, the Resurrection, the four Noble Truths, and the superiority of the Red Sox to the Yankees. And, as we all know, beliefs can be true or false, whereas knowledge is unassailable. In contrast, faith elevates belief to a religious level. Faith is a total, engaged response to and identification with myth that annihilates the critical distance between it and me. It is through the eyes of faith that one sees whatever one sees, not as a proposition that can be true or false, but as the way things are. Faith engages heart and soul. It is not enough to know about; one must directly experience and respond through the auspices of faith.

the postmodernist

Thursday, July 29, 2010

Christmas

Nihilism too is a culminating mythology of a long skeptical tradition that says that there is no meaning in an otherwise objective or neutral universe without purpose. Ironically, the myth of a meaningless universe is itself a way of infusing meaning into the experience of meaninglessness. According to this myth, we gain authenticity, dignity, and meaning by honestly and bravely accepting that the universe is without intrinsic meaning. The myth tells us that we are superior to those who live false, inauthentic lives by believing in one myth or the other, whether that myth be the American Dream or a socialist revolution. There's nobility and art in creating meaning in an otherwise meaningless universe. Paradoxically, a mythic strategy is effective for investing life with meaning even when the myth is telling us there is no meaning.

take the good, without the bad

the cost of modernity

If the questions “Why?” and “What to do?” find an answer neither in our biological instincts nor in the secondary instincts of our postmodern culture, then what to do? Where do we go from here? What do we do when the truth is exposed and the truth is that life is meaningless?

Several, ultimately futile possibilities exist on both the individual and social levels for at least temporarily denying meaninglessness and its associated depression. One strategy is to return to our primary instincts. The pioneering sociologist Emile Durkheim described the failure of culture as deculturation, a state, he said, that reduces its victims to the animal level of chronic fighting or fornication. If I find direction or meaning neither in culture nor in more self-conscious attempts to answer the why questions, then I may find solace in my body, emotions, and pure, unmediated experience. From the perspective of these strategies, meaninglessness is not the problem; thinking self-consciously is the problem. Avoid or deny the questions, concede that you are nothing more than an instinctual animal in an indifferent universe, and you've solved the problem. Alcoholism, drug addiction, sexual obsessions, and adventurousness—in which meaning remains, but only while engaged in extreme and risky activities, including violence—have all been attributed to misguided and finally self-destructive attempts to suppress the question of meaning by drowning in instinctual behavior. The climber Mark Jenkins articulates perfectly the experience and joy of losing oneself entirely in the body this way: "At this moment, all I know is movement. I'm not even thinking; I'm just climbing. I shut down the brain and let the body be what it is: an animal. Unbeknownst even to myself, somewhere high on the Sheila Face, I unlatch the cage. . . . The cage door swings open and out steps the beast.

On a social level, as early as 1941, Erich Fromm was writing about our collective Escape from Freedom. Why the need to escape? From what are we escaping? Fromm argues that a long history of liberation—from first nature, race and family, the authority of the Church and then the state (the Reformation and the rise of democracies, for example)—terminated in the achievement of individual freedom. But having attained that cherished goal, the question became "freedom not from what but for what?" Having progressively rejected the guidance and authority of revelation, community, tradition, and reason, freedom becomes a burden, and we have the absurd situation of being free to choose anything we wish but having no choices worth making.

Knowing neither what we must do nor what we should do, nor even what we wish to do, Fromm argues, we typically look for clues by watching what others do, or willingly abdicate the burden of freedom by reverting to the authority of others, whether the latest guru, pop celebrity, or political leader. Conformity and authoritarianism are thus collective strategies for relieving the anxiety that absolute freedom elicits. We willingly exchange our anxiety and freedom for compulsive activity and the answers provided by others. Conformity to the cultural norms modeled by members of our family, friends, and associates or obedient loyalty to the goals of our leaders and nation protects us from the debilitating experience of nothingness resting at the heart of modernity.

Philosophically, the modern, debilitating ideology that humankind is nothing but a complex mechanism of chemical reactions or social forces and its attendant experience of nothingness is, itself, the culmination of a long skeptical tradition. The notion of the Absurd arose when humankind's desire for meaning and purpose confronted the indifferent universe that the skeptical tradition projected. On the one hand, modernity was a necessary prerequisite for the emergence of the existential vacuum, and thus a source of the problem. On the other hand, modernity is also a solution. If one believes that the universe is indeed indifferent and without purpose, then the absurd is merely nostalgia for a world that never existed.

Wednesday, July 28, 2010

Honor

Values: